Originally posted on The CityFix.

By Darío Hidalgo, BRT+ researcher.

Eighteen years ago, I was deputy general manager of TransMilenio S.A., the city agency running Bogotá’s brand new bus rapid transit (BRT) system. It was amazing to be there at the start of operations for this system knowing that it took just three years from idea to implementation.

On our first day, December 21, 2000, we had 23,000 riders, a figure that grew very rapidly in the following weeks. Initial service was very limited – just 14 kilometers (8 miles). The large articulated buses were just arriving, some stations were not operational, the fare collection system was not functional. But, still, it was new, different and captured people’s attention and imagination.

News of the system spread like wildfire. Everyone wanted to try it, and, at first, public perception was very positive. In February 2001, the sociologist Alfredo Molano wrote in his weekly op-ed that “the system proved that a fair capitalism was possible, respecting rights of the people, of all the people.”

But TransMilenio’s teenage years have been more problematic. The expansion of services has slowed considerably, even as demand continues to increase, leading to crowding, inefficiency and declining service.

The Largest BRT System in the World

TransMilenio grew-up very quickly. Each month of 2001 brought new stations and more buses. I rode the lines up and down with my six-month-old daughter, impressed with the ease and quality of transit. It was great to see such a positive change in my own city and to be with so many happy people.

By 2002, the system reached 42 km, including a 1.7 km transit mall downtown, where there was only walking and public transport. User satisfaction remained above 90 percent during the first three years of operation. Agency staff were committed to delivering a service that was respectful of life, diversity, and time, and that was affordable for users and the city.

Building a high-capacity, mass transit system based on buses was a novelty, not only for Colombia’s capital, but for the whole world. It was inspired by bus systems in Brazil and Ecuador, but the BRT in Bogotá was like Curitiba’s on steroids. Bogotá had much larger stations with up to five bus docking bays, double bus lanes for passing, and express and local routes, making TransMilenio the largest capacity BRT system in the world. Before TransMilenio, the busway on Avenida Caracas, a main arterial road, carried 35,000 passengers per hour in each direction; the new BRT was able to orderly carry up to 48,000 passengers in each direction, amounting to 2.5 million passengers each day. It was also much safer: the old busway had 64 fatalities in 1998; the new BRT had 8 fatalities in 2001.

Bogotá’s achievement was not only a technological leap, but an institutional transformation. Before TransMilenio, public bus transport in Bogotá had very dispersed ownership – basically one owner per bus. They worked very extended hours without any benefits, competing on the street for each passenger. With the BRT, however, companies received limited time concessions and were required to acquire the bus fleet, maintain it, and hire drivers and staff while complying with strict labor rules. Companies were now subject to rent, value added taxes, and local taxes on industry and commerce.

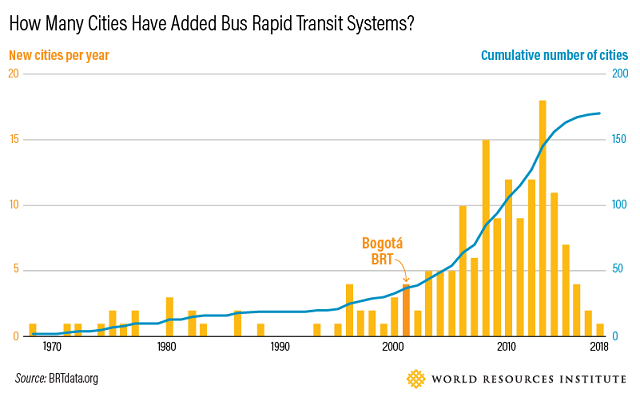

TransMilenio’s initial success was extensively recognized. Many cities initiated similar projects adapted to their local context, including in Colombia (6 cities), Mexico (7 cities), Guatemala, El Salvador, Peru, Argentina and Brazil. Bogotá’s influence also permeated outside of Latin America, reaching China (20 cities), India (7 cities), Indonesia, and has been used as a reference for planning bus systems in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and Africa.

Across the word, there are 170 cities with BRTs, and 140 were implemented after Bogotá. BRT corridors are seen as necessary tools for modern transit in developing cities, and are therefore common in alternative analysis for mass transit corridors.

Growing Pains

But even though the first few years of TransMilenio were brilliant, its teenage years have proved challenging. After building 82 km in TransMilenio’s first six years of operation, the city only built 29 km in the following seven years, and just 3 kilometers in the last five years. The most recent addition in December 2018 was a 3.6-km cable car, TransMiCable, in the mold of Medellín’s Metrocable, which is integrated into the TransMilenio system. Reduced political support and growing institutional complexity have led to protracted approval processes and slower expansion overall.

Meanwhile, travel demand has continued to increase, overcrowding buses. Maintenance and operational efficiency have declined, and replacement fleets are now eight years overdue (requested in 2011 but will only become functional this year).

In the face of these challenges, user satisfaction plummeted to 13 percent in 2018. TransMilenio faces similar issues to other mass transit systems, including Mexico City’s Metro, New York’s MTA and Washington’s Metro. Significant investments, timely maintenance and continuous expansion are needed to keep up service quality.

TransMillenio’s adulthood comes with great expectations. What started as a system with so much promise has left much to be desired. But the potential is still there. Fleet renewal will start soon, brining larger capacity and lower emissions buses. Most of the new fleet will have natural gas engines, and new diesel buses will be required to have filters. Many stations will be expanding and services reorganized.

Alongside many Bogotános, I hope the system improves promptly – integrating with metro, cable-car lines, regional rail and electric buses, too. I hope Bogotá continues to be a global reference for sustainable mobility, not just for what it did two decades ago, but what it can do today.